Gallery

After All

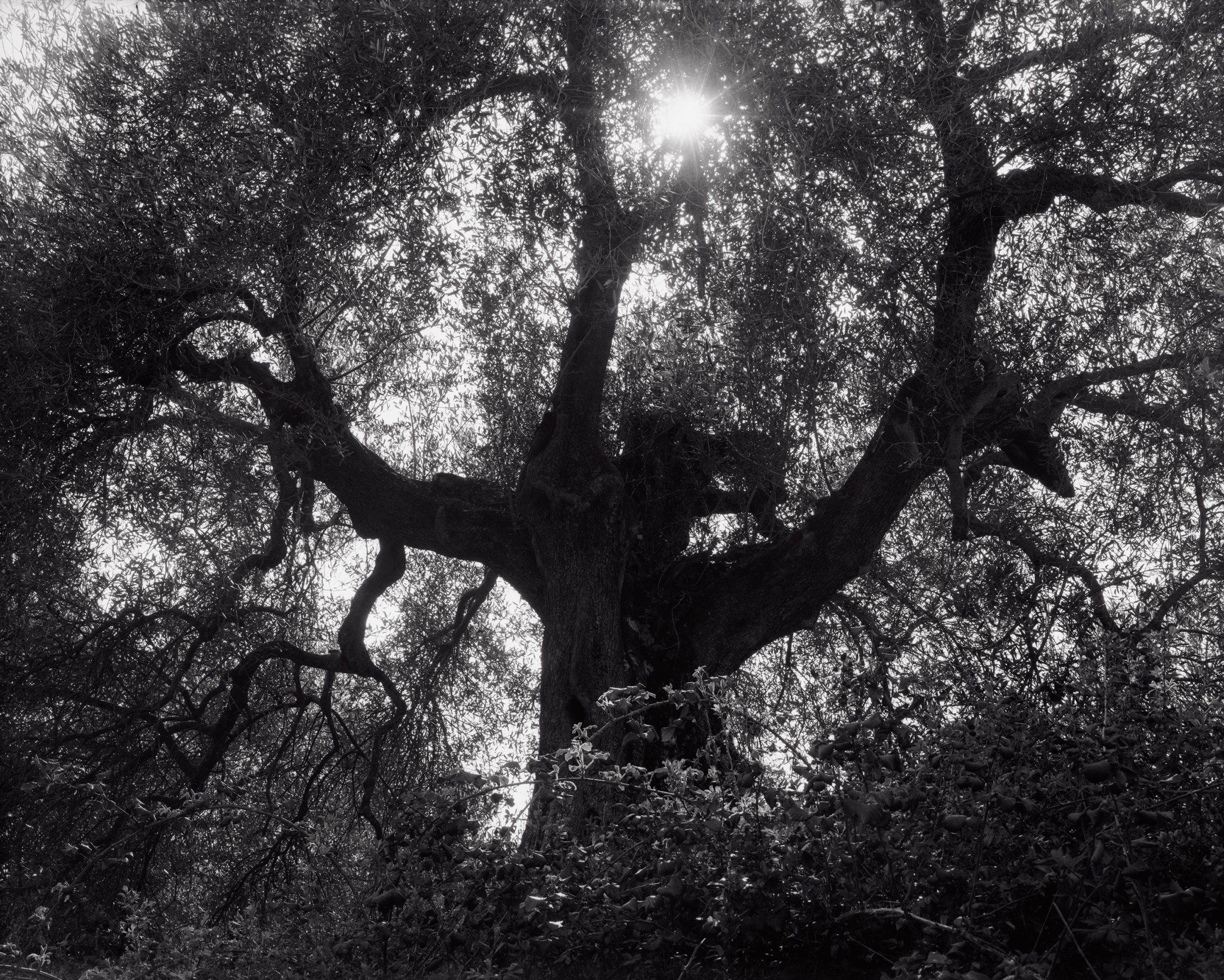

Many millennia after forests began doing it, humans are learning that trees have complex vascular, mycorrhizal, fungal, electrical, and pheromonal ways of networking and relying on one another for species survival. They are communal, familial, and have symbiotic relationships with a diverse range of organisms in the forest floor and with one another. Trees share nutrients, light, threat signals, adaptive responses, and become stronger through community than when thinned or separated. Undamaged forests have collective knowledge and live in interconnected cooperation, not in competition as once we thought, but they instead have evolved to share their needs and resources. Their matter and circuitry existed within their ancestors before they were fully formed, and they continue to feed young saplings and a vast array of organisms through their lives and as they decay.

Humans have learned very little from forests and have learned it so late. But our nature, as often demonstrated by the newly and most alive humans, is a similar embodiment of connection, empathy, resiliency, and hope. The symbiosis now urgently required to sustain our habitat and one another will require an attentiveness to the interdependence and innate potentials of humans, forests, and our entanglement with all species.

These images are reflections on fear, awe, uncertainly, and hope. Figuratively and literally, our hopes for a future rest on the contrast and connectedness of my two subjects, ancient, carbon-capturing forests and young idealists and activists; both are threatened by the impact of consumerism and greed, and both are essential in rescue from catastrophe. These hopeful figments are studies in beauty, fear, and anxiety, and are presented to emphasize our inherent fragility and connectedness.

Via

While walking, we see and are seen, we engage ourselves with our neighborhoods, pause to notice bits of the world we may otherwise not, and we experience the world at the human pace. These images were made amidst the communities and social rituals of others in an attempt to embrace a slower pace and a more communal spirit. As a Midwestern American, I too often travel by car, missing so much as I go. These images are made during rare and distant opportunities to immerse myself in the minutia of my surroundings, to see and be seen, and to navigate the world at a more appreciative pace. I photograph in Italian and Spanish historic town centers where walking is the primary mode of transportation and daily visual experience and expression are everywhere emphasized. Through the context and tradition of strolling through historic streets, I observe my global contemporaries and record visual fragments of our combined cultures.

Near

My search for poetic associations between place and experience is facilitated through my fascination with the photographic object. A photograph as image, memento, and referent to absence is physically touched by the past yet allows for a new experience through the photographic object. Photographs as tangible evidence/residue from events, experiences, relationships, and places offer me the ability to associate the specifics of the past with image/objects. That layering of characteristics inherent in the photographic object provides the basis of my approach to image-making. By using the specifics that photographs can render, I attempt to connect places and ideas through visual associations.

Pilgrims

I travel with a large camera, my excuse to encounter other travelers, artists, and local passersby. The resulting portraits are evidence of the intervals of stillness, the subtle negotiations, and the mutual understanding of the power of photographs. The photographic event is full of potential, each fraction of a second slightly different from the next. Mysteriously revealing so little while describing so much, portraiture offers me an enigmatic method of exploring the world, its residents, and the distance between us.